2/29/24

Studio Visit

In the Studio with Noormah Jamal

CMA Resident Artist Noormah Jamal discusses her favorite art tools, her Pakistani childhood, and learning to paint in the Mughal Miniature style.

Click to expand media gallery.

As part of CMA's Residency for Experimental Arts Education, Noormah Jamal teaches art to fifth graders twice weekly at Children's Workshop School, a progressive public elementary school in NYC's East Village. Below, visit Noormah in her studio and get a glimpse at her artistic process.

On a Perfect Day in the Studio

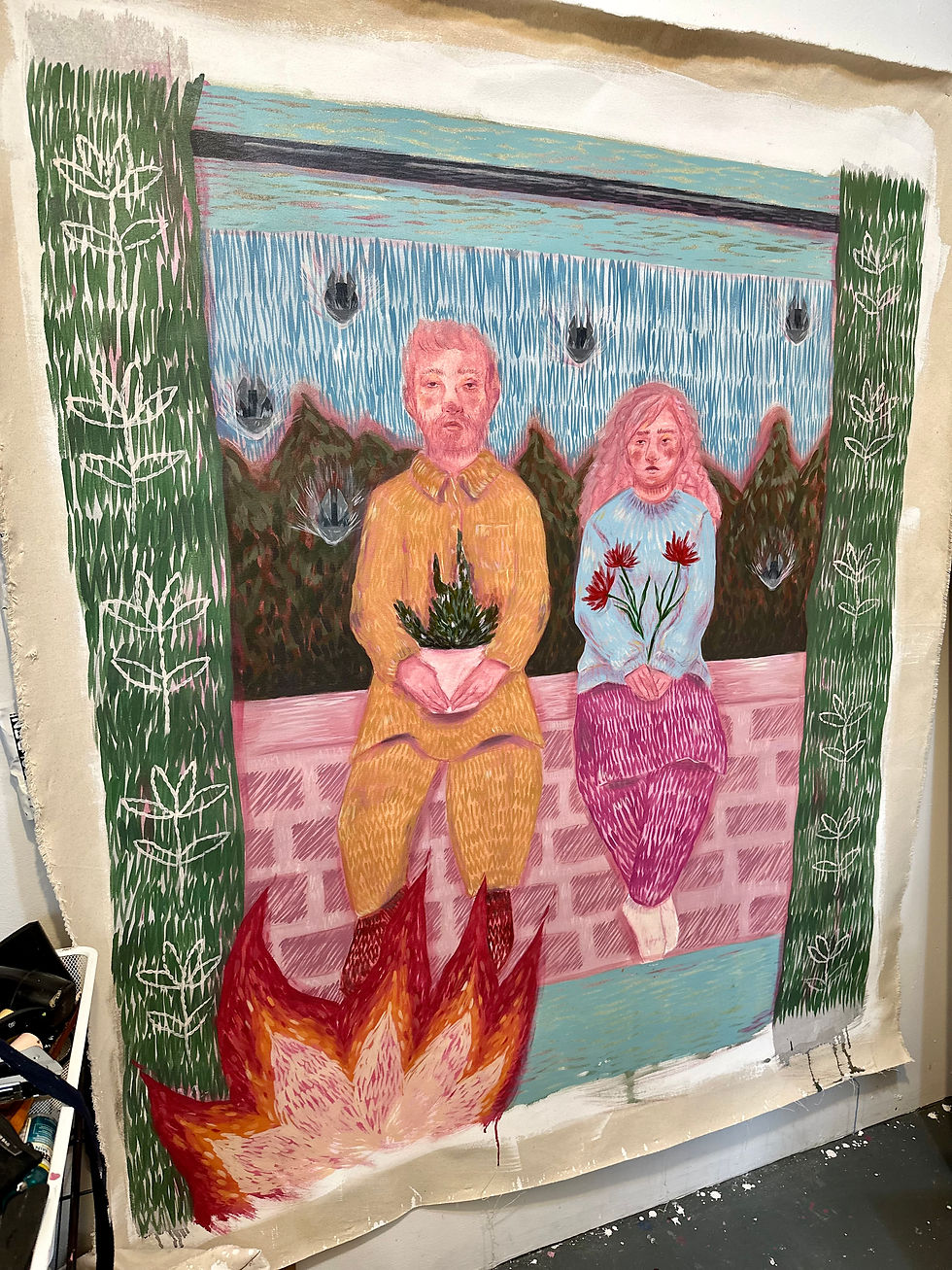

I come to my studio at least six days a week. I've been experimenting quite a lot recently. Initially, my practice was primarily in gouache. During grad school at Pratt, I developed a new style that incorporated my training in miniature painting. It was quicker, and I was able to work on a much larger scale, and acrylics worked really, really well for that.

The line work that I’m doing is a finishing technique to achieve the flatness of gouache. I flipped it, in a sense, because I want to create a certain vibration and sense of urgency in my work. Instead of flattening, I try to show movement, almost like a woodcut. It’s very directional.

I’m jumping back into gouache again and seeing how the techniques that I used for acrylics translate to gouache. I enjoy working in acrylics, but the flatness of gouache really does something for me. You can also layer on with pencil colors.

Her Favorite Tools

You know when people have acrylic nails, and they use that really tiny drill? That’s what I use for my air dry clay. You have to wait for it to dry and not crack into a million pieces. Once it’s bone dry, I sculpt with that tiny drill.

I found this really stiff brush that I love. It allows me to make marks that I couldn’t do with softer brushes. With my early works, a lot of people thought I was doing line work with markers. The stiff brush helps me achieve that look.

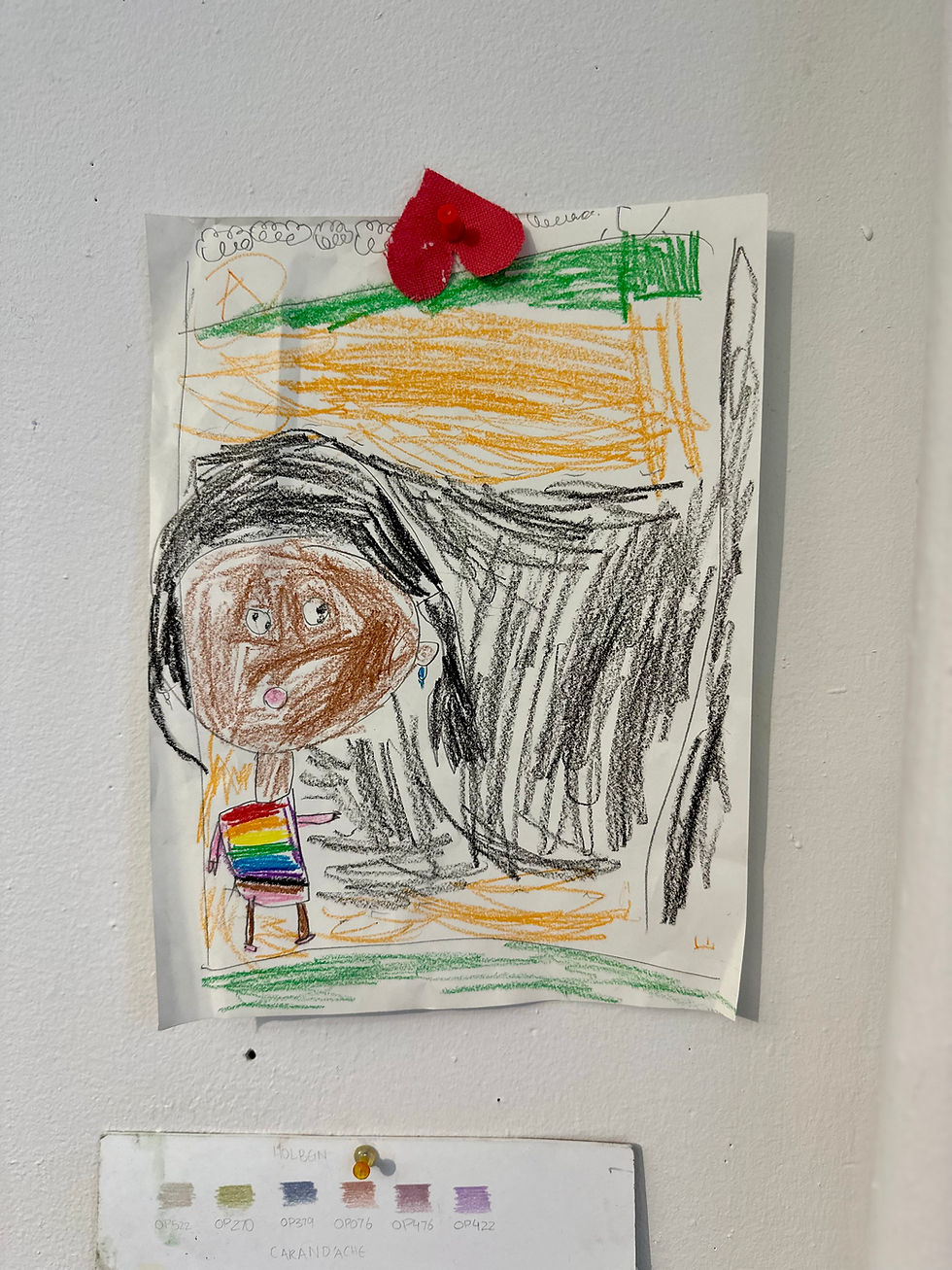

This is a work by one of my students from the Bushwick library where I also teach. It’s a drawing of me. The funny thing is that I wasn’t even wearing blue earrings that day. The student looked at me and said “blue would look good on you.” It made my heart melt.

Painting Miniatures

I attended undergrad at The National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan, where we studied painting, sculpture, printmaking, and miniature painting, which is an ancient South Asian, Central Asian, and Iranian art style. The National College of Arts is the only institute in the world, I believe, that grants undergraduate degrees in Mughal Miniature painting.

Once you have the gouache paint washes on the paper, you do the finishing with a tiny brush that is made of squirrel or cat hair. It has to be hair from the tail because it holds water in a certain way without collapsing. This gray brush is from Iran and it’s made of cat hair. The other two are handmade squirrel tail brushes. The holder (between the hair and wooden part) is the tip of a pigeon's feather.

When the Mughal emperors took over India, and set up their royal court, they brought their court painters with them, so many traditional miniature paintings depict the life of the emperor or great battles that took place. These paintings used a lot of gold leaf and were often very small and held together in books. “Neo miniature” is the name for the contemporary style. The size has increased, but the level of flatness and finishing with tiny dots and lines remains. The goal is that it should look as perfect as it can be – staying true to the artform.

Other students would call our department "the boot camp” because you have to pick up the technique very quickly. The first year was copy work, where the professor would show us ancient paintings that we had to replicate. You use gouache on wasli paper, which is basically multiple cotton-based papers sandwiched on top of each other. It’s very thick, so it can take a lot of water and gouache on top of it. After the copy work, we were encouraged to develop our own style, but we still had to adhere to the miniature aesthetic. As soon as I graduated, I changed my style, because I knew that my miniature training would be a tool, but not a box that I’m confining myself within.

I came to Brooklyn to attend grad school at Pratt. The distance really helped me. Back home, it's considered a pity if you change your style post-training. Other artists feel that it’s a shame that you’re not sticking to the tradition and the classics. But that's not the type of artist that I am – I love experimenting and playing around. That’s why I love teaching kids. Kids have incredible bravery when they’re dealing with new mediums or techniques. They inspire me not to limit myself.

My scale and material also changed once I came to Pratt. Being in that “boot camp” for so long was integral to my practice, and I still borrow a lot of elements from that training. You can see the traditional 2D flatness and angles in my work, except I also incorporate motion and organic brushstrokes.

On Oral History, Censorship, and Character Creation

I have an archive of old family photos that I get inspiration from. The ethnic group that I come from are called Pashtuns, and they have more of an oral history than a written one. I also draw from my family’s own oral history – although obviously there’s a lot of embellishment, and things often go missing depending on who’s narrating things. I get really inspired by conversations with my family.

The work I created in Pakistan relied on symbolism and a child-like aesthetic because I was having to deal with censorship. Kids can get away with saying so much. Since moving back to the United States, the news has played a big role in my life. I started religiously following the news, and the more I watched, the more I realized that media bias exists in the United States equally. It’s important for me to be here and witness it. It’s sad that the whole world deals with media bias, but it makes you ground yourself and realize what you’re up against. You have to educate yourself, do your own research, and not blindly trust everything that’s coming out of someone’s mouth.

The figures in my work are very aware of the situation they’re in. The more you look at them, the more you see. I also have very blatant associations with the symbols that I use. I tend to drown my paintings in symbolism so the viewer can get a lot out of it without me necessarily having to spell things out.

In terms of creating the characters, I free draw a lot, so I’ll merge images on top of each other. The current series I'm working on are figures based on news anchors. They’re an amalgamation of multiple people from different countries. This one is a play on a Pakistani news anchor and Christiane Amanpour. The guy at the bottom is a mix of an Indian and Pakistani news anchor. I have a show coming up and I’m planning to do a whole wall of them, much like the television screens in a grid format at Best Buy.

This work is based on a loose drawing of a photo I found a few years ago of my sister and cousin watching television. You can recognize the pose of being sprawled out in front of the TV.

We saw a lot of instability because of random acts of terror in my hometown of Peshawar when I was young. I spent most of my early teenage years indoors because of this, so I know a lot about pop culture. People say that I’ve integrated so well into American society, but that’s because I had nothing else to do. I was either drawing or watching television – constantly taking things in during those years.

I attended art classes at my school until my O-levels, which is about 10th grade. For my A-levels, I went to a school in another city because art was offered there. For my undergrad, I then moved to another city. I guess I’ve been chasing the arts my whole life!

Mother Tongues

My mother tongue is Pashto, but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu. In schools, we’re taught Urdu and English. I ‘think’ in one language when I’m excited, and I think in another when I’m upset. I often talk in all three languages together. I’ll start a sentence in Pashto, and it’ll end in English. When I first came to the United States and had to depend solely on English, I had to slow down and think of substitutions for words, because I was so used to jumping in and out of languages.

Even though I’m fluent in my mother tongue (Pashto), I didn’t learn to read or write it in school. After undergrad, I had to teach myself how to read and write the language. Luckily, the alphabet is the same as Urdu, with a few more characters. It was strange to teach myself how to read and write a language that I’ve been familiar with my whole life.

On Moving Back to Pakistan

I plan to move back to Pakistan at some point. I’ve been looking for jobs in children’s education because I want to start something in my village related to that. My sister works with NGOs and does a lot of field research, we thought that would be a good mix.

The Malala Fund does a lot for that part of Pakistan as well – arguably the most famous Pashtun is Malala. My plan in the next 5-7 years is to affiliate myself with one of the foundations to test out certain lesson plans. There’s no government funding for the arts in Pakistan, so there’s nothing to support artists, in that sense.